PHash Blog

perceptual hashing information

AudioScout™: Audio Fingerprint Retrieval System

30 Apr 2019 - by starkdg

Audio track recognition is about identifying short audio clips among a larger collection of indexed tracks. To get a better idea for what it is:

What it can do:

-

You hear a song playing. It sounds familiar, but you can’t quite put your finger on it. You reach for your cell phone and manage to record a few seconds. Submitting the recording to a track recognition system can identify its source.

-

Or: You are constantly receiving new audio tracks to add to your ever expanding collection. The main problem is duplicates are mixed in with these new arrivals. File names and metadata may provide an occasional clue but are inconsistent. Even the raw data come in varying formats and levels of quality, so a straight bitstream comparison is of no use, not to mention cumbersome. Even if you have virtually unlimited storage, just storing duplicates is no way to bring order to your collection. You need track recognition.

-

An invaluable tool to monitor how often you encounter specific audio signals and collect relevant statistics.

What it cannot do:

-

Identify a song from a particular performance, or a story from a particular narration. For example, various renditions of a popular song.

-

Learn to recognize spoken commands - like “tell me”, “define”, or “what is the weather?”. Conceivably, you might think you can index reference tracks of such commands and expect queries to be correctly identified as such. This will not work. Two different people saying a word amounts to two different tracks.

-

Recognize someone’s voice or a specific instrument. This is Voice Recognition, not track recognition.

-

Any kind of semantic analysis. This can be done with various machine learning techniques. Nevertheless, it is still an entirely different problem.

While track recognition can still be robust against various distortions, audio that you expect to be matched still needs to be from the same source.

A Reliable Solution

This post introduces the second iteration of AudioScout™, an audio track recognition system that, while admittedly not the optimal or latest algorithm, is yet not without its advantages. Indeed, the basis of the algorithm has been around for at least two decades now. You can read more about it here haitsma, kalker, 2002, but I will proceed to give you my peculiar implementation of it. It is a surprisingly simple and elegant algorithm.

First off, some of the advantages:

-

For one, it does not depend on a giant corpus of audio files to train the model. There are no machine learning techniques involved. The algorithm is entirely deterministic and not data dependent, and it does not require constant fine-tuning.

-

Relatively low storage overhead to index the collection. The audio fingerprints consume only 1.5% of the space of audio files, so indexing audio content does not consume much additional space relative to the size of the collection.

-

Recall accuracy - the percentage of correct results for distorted queries - is at least competitive, if not ideal. In my tests, I have seen near 95% accuracy for 4-6 second queries. Of course, this all depends on the magnitude of the distortion, but these tests allowed for a severe level. Precision accuracy - or number of false positives - is quite favorable too. False matches are rare to infrequent, but can be dismissed by thresholding the confidence score that is returned with all results.

Audio Fingerprinting Method

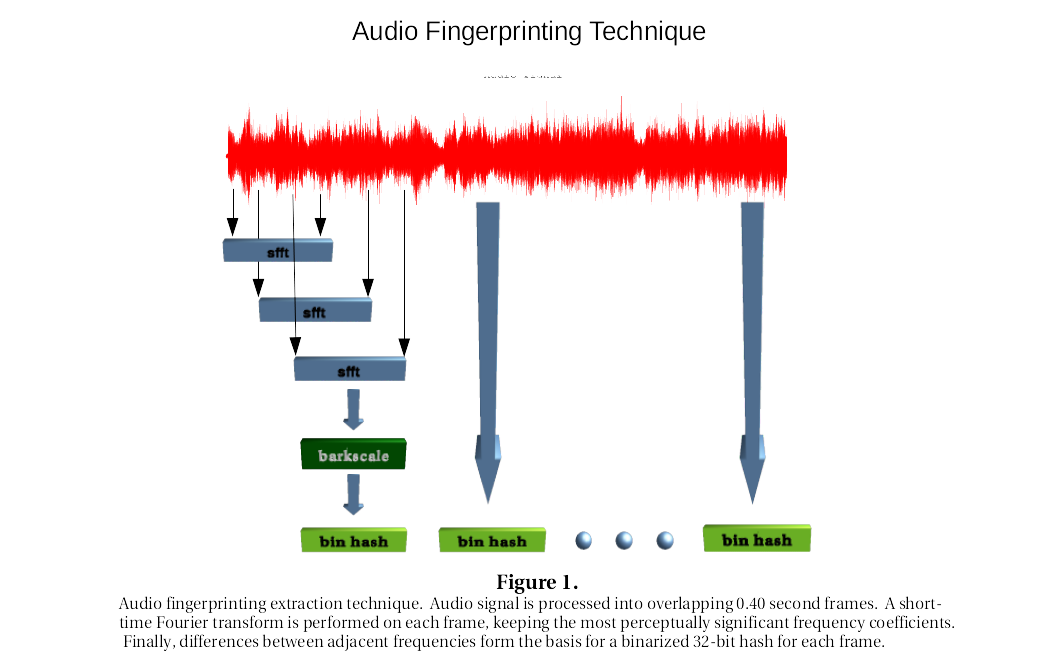

The fingerprinting method is summarized in figure 1. Condensed fingerprints are extracted from the audio. The signal is segmented into tightly overlapping frames, each of 0.40 second duration. Overlapping increases the chance two sequences of hash frames can be matched. A short-time fourier transform - stft - is applied to each frame, and 33 perceptually significant frequencies are selected. The 33 frequencies are used to make a 32-bit binary hash, h, according to relative differences between adjacent frequencies:

$h[i] = 0$ if $freq[i] - freq[i+1] < 0$

$h[i] = 1$ if $freq[i] - freq[i+1] > 0$

for i = 1 … 32 and frequency magnitudes, $freq[j], j = [1 … 33]$

Once the binary hashes - or binhashes as referred to in figure 1 - for a pair of audio tracks are calculated, substring matching can be used to see if any of the binhash frames from one signal match up with the frames from another by looking for sections where the bit error rate stays below a predetermined threshold. Bit error rates can be ascertained by a simple normalized hamming distance - the percentage of bits that differ.

But what makes this technique especially powerful and robust to distortion is that even more information can be gleaned from the absolute differences between adjacent frequencies. By ordering these differences from the smallest to the greatest in absolute value, and keeping track of the original position indices, we then have a rough idea for which bit positions in the array are most likely to flip through distortion. These position indices can then be saved in 32-bit integers by setting those positions to 1. With one 32-bit integer for each binhash, this means a parallel array to describe which bits are likely to be toggled in distortion.

While this does double the payload for each fingerprint, that payload is still only 3.0% of the original signal, since the number of bin hashes is only 1.5% of the audio signal. What is more is that these toggles only have to be computed for the query signals of a few seconds in duration.

These toggle arrays can then be used to find extra candidates to compare to prospective matches in our substring matching algorithm. For each binhash of a query signal, just try all the permutations for flipping the bits indicated in the toggle. If just one candidate for a given frame falls below a given threshold, it can be considered a match within the prospective sequence. This greatly increases the odds for finding a match.

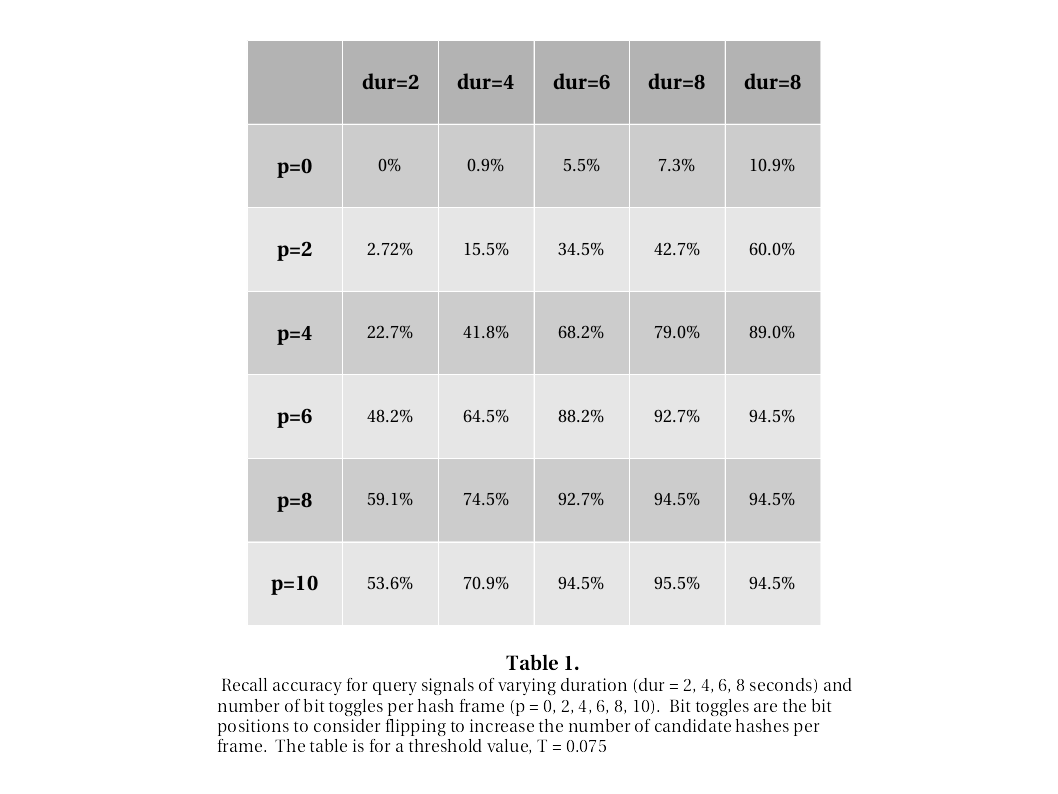

Of course, this comes with a catch. As you increase the number of bit toggles to consider - lets call it p = 0 to 32 - the number of candidate hashes explodes exponentially. In other words, while p = 1 means $2^1=2$ extra candidates, p=4 means $2^4=16$ extra candidates, and so on. So, it is imperative to keep a relatively low value for p to avoid overburdening the matching algorithm. For our purposes, a value of p = 6 seems to mark a good upper limit.

Fingerprint Indexing

AudioScout™ stores the fingerprints of all tracks in a reverse index. A reverse index is basically just a hash table, where the binhash is a key pointing to a data unit containing the unique track ID along with sequence information. This sequence information tells us where the binhash fits into the track’s sequence.

In this way, unknown queries can be checked against the index. Each binhash of a query can be looked up in the index. If a match is found, the match is stored in a list to track the number of finds for that unique ID. More candidate binhash’s are generated from the toggle information by permuting all the marked bits.

Retrieval performance is fast, taking no more than a second or two to identify 2 to 6 second queries. Obviously, the longer the query, the longer the wait time.

The index can hold a virtually unlimited number of tracks.

Test Results

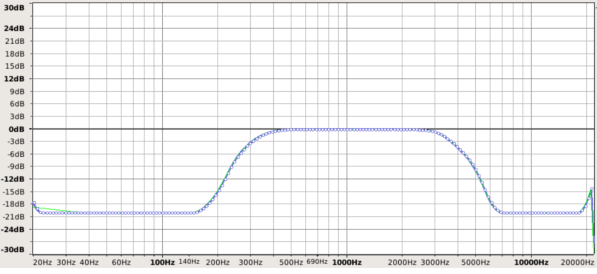

To test the AudioScout retrieval system, over 1200 music cd tracks were indexed. From these files, 15 second clips were chosen randomly to use as query signals, applying a telephone-like distortion and adding a 0.05 amplitude noise on top of the signal. This seems to be a fair if somewhat extreme level of distortion one might reasonably expect.

Here’s a plot of the distortion used:

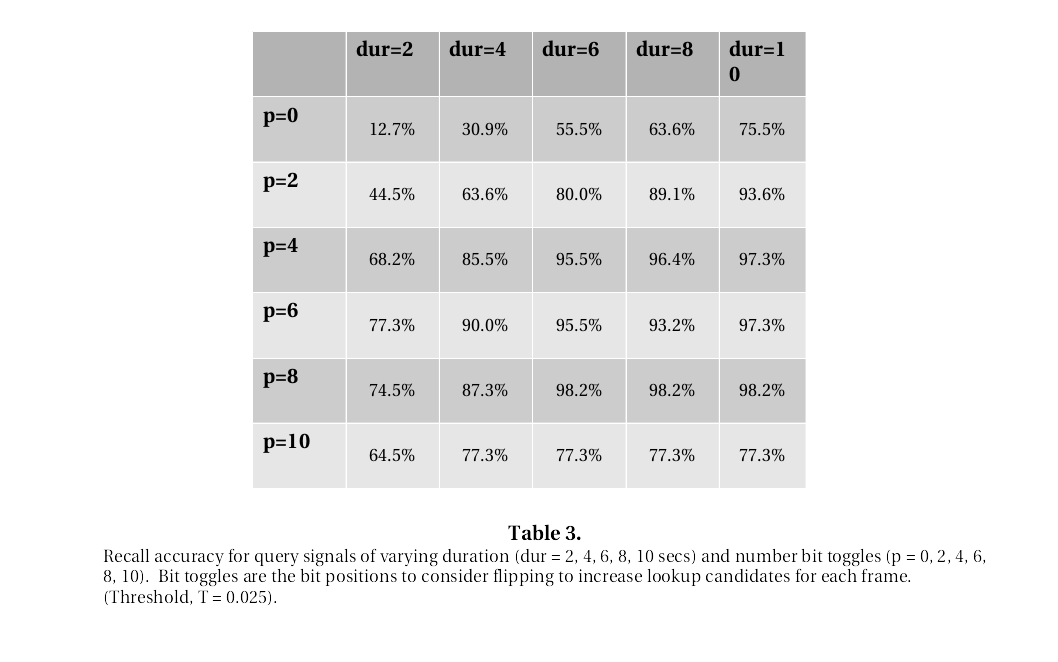

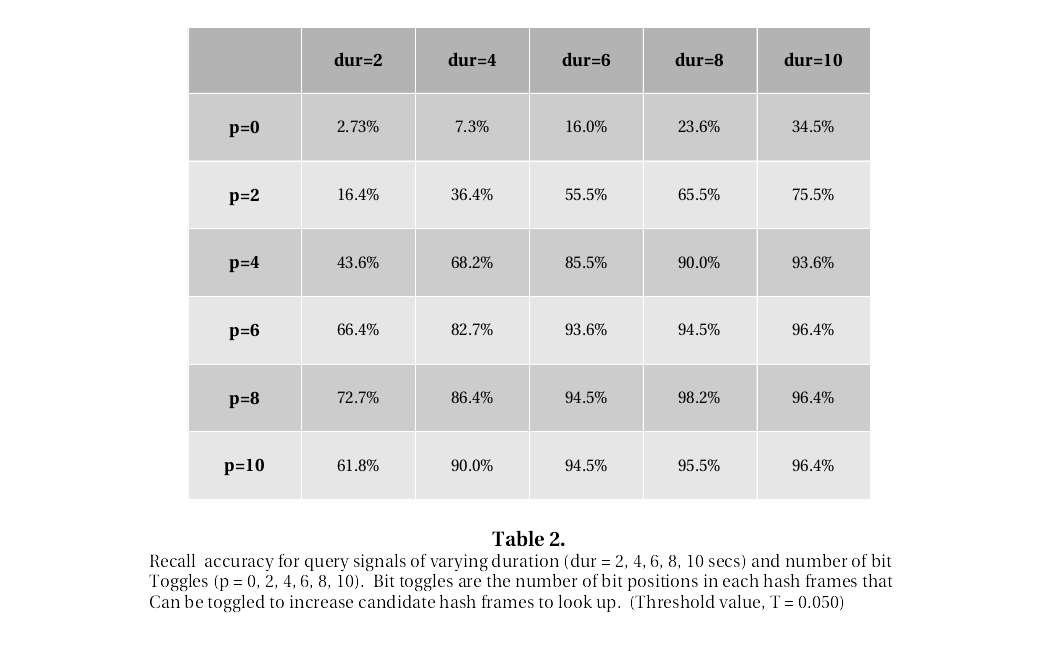

The following tables show the classification accuracy for the test queries. The entries are the percentage of queries that obtained a correct matching result. Queries are performed for various signal duration - across the columns - and for various number of bit toggles - across the rows. There are three tables, one for each threshold (T = 0.025, 0.050, 0.075)

As you can see, almost 95% accuracy was obtained for 5 second query clip using a p=5 number of toggles.

Undistorted queries - that is, queries from the indexed files that are not at all distorted - do return a 100% correct match rate. So, the clearer the signal, the better the recall rate.

Code

Access to the index is controlled by a server program - Auscoutd. It exposes network interface through which client applications can submit new audio tracks as well as query unknown tracks. A demo client program is included, called AudioScout. The github repository can be found here:

The api for creating client applications contains the audio fingerprinting functions. The github repository can be found here:

Here’s the github repository for the c library and java bindings for reading audio data:

Comments and suggestions are welcome on the issues page: